Five years after the 181 Women’s Helpline was launched as a comprehensive support system for women, here’s looking at what it takes to build networks of support and solidarity that are sensitive, survivor-centric and just.

December 16 has become an epoch of sorts in our collective memory, and in the movement to end violence against women. It is unfortunate that everyday practices of patriarchy do not irk and outrage us as much as they should, it is equally unfortunate that rapes and murders of women in the rural hinterland do not make it to our news and our conversations.

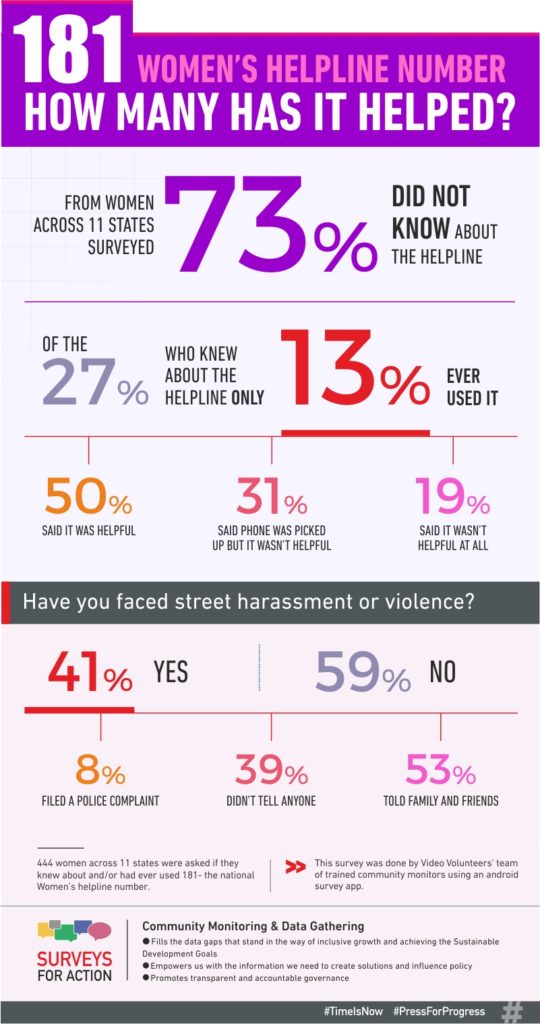

After the incident, apart from concrete changes in the law, the government also set up a central helpline number, touted as a one-stop crisis centre for women across the country - the 181 Women’s Helpline. This year, in the build-up to International Women’s Day, Video Volunteers decided to look at the existence and the effectiveness of this helpline number. Our Community Correspondents rolled out a survey to over 400 women across 11 states. The women were asked if they knew of the helpline, if they had used it and if they had found it helpful.

It was no surprise that five years after the helpline was launched, only 27% of the women surveyed had heard of it. But it was not the statistics but the stories behind them that were telling of the gravity of the problem.

“Police ke paas toh gaye they lekin report darj nahi kiya..kaha ki bezzati ho jayegi, mukadma mein phas jaayenge.”

("I went to the police to file a report but they didn’t file it..they said that I will be insulted/shamed, and will get caught up in court cases.")

Surely the 'Delhi gangrape' case riled the masses, grabbed the media's attention and pushed lawmakers into taking some action, but did it change the way in which the state's support network responds to women in distress?

A woman who comes forth to speak against injustice still faces the risk of being shamed while a woman who dies without getting a chance to speak becomes a braveheart - Nirbhaya, the fearless one.

But let’s take a step back and revisit the survey.

59.4 % of the respondents actually reported that they have not faced sexual harassment or violence. It would be convenient to say that this is a heartening figure but we don't know what comes under the umbrella of sexual harassment for the respondents, or if they chose to not report it in the survey. Not reporting or even talking about instances of sexual harassment is no surprise, definitely not when a woman is told that she should not report a case because she will be shamed.

Of the 40.5 % who said yes to having faced sexual harassment, which is 180 women, majority of them spoke to friends and family about it, followed at a close second by those who didn’t tell anyone. Less than 8%, or 14 women, filed a police complaint. The National Crime Reports Bureau (NCRB) figures that shock us every year are only this tip of this iceberg.

Before rolling out the survey, we tried an internal exercise-- calling up the helpline ourselves. When Yashodhara Salve, a Community Correspondent from Mumbai, called up the helpline, it connected her to a centre in Gujarat, and the centre could not redirect her to the one that could help her.

For many women surveyed and interviewed, there seemed to be a confusion over what the helpline number was. Some women said that they knew of a helpline but didn’t know what the number was. Some dialled 1091, the helpline which was set up in 2004, others dialled 100, the universal number for calling the police in India. Even after five years, the new helpline number does not have enough visibility.

“Creating visibility for the helpline number is important, and this should be done not only in convergence with non-governmental stakeholders but also with state schemes like Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao”, says Taranga Sriraman, Strategic Coordinator at the Resource Centre for Interventions on Violence Against Women (RCI-VAW) run by Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, through Special Cells for women and children.

But what we found more interesting was that of the 122 women who did know of the helpline, only 16 women had actually used it, and only eight found it useful. The reason? Lack of faith in the system. And not because women are baselessly cynical about government services but because of experiences that have deterred them.

“Ab bharosa kya, ek baar toh ho gaya hai toh thoda sa darr baith hi gaya hai.”

("How can we have faith now, after having gone through the process, I am obviously apprehensive.”)

When Community Correspondent Jahanara Ansari spoke to a constable in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, he was of the opinion that women should not register complaints in order to save themselves from being shamed. He adds that even educated families avoid coming to the police and prefer 'settling' matters at home.

When asked which cases he would register, he says, “In matters where a case should be filed, we file one; in the other, we make them understand.” Women affected by harassment and violence are often made to ‘understand’ that their families’ reputation and honour may be at stake, they may land up in long legal battles or they must simply think of their relationship. Marriage and family continue to be seen as sacrosanct.

While these demand a change in attitudes towards gender and patriarchy, difficult to inculcate with immediacy, what can we do to build trust and strengthen the existing system, starting with the helpline?

Sriraman is of the opinion that good quality of response to callers is the main action that can be taken. “World-over, telephonic helplines’ data shows that a massive proportion of calls received are 'checking-out' calls made by common people to see if the helpline actually works and what it is meant for.” She also emphasises on the need for trained professionals and a survivor-centric approach, along with the importance of data confidentiality.

The helpline, technically, is a resource that women can turn to after an incident has taken place. But like the Special Cells whose objective is not only to empower women to speak up in vulnerable situations but to build a sense of agency, the helpline too should be a support system to fall back on and a system that strengthens women.

International Women’s Day comes with a long history of the struggle for rights, which began with “working” women’s rights but is today a day to acknowledge how far the various movements for gender equality have come, to recognise the roadblocks ahead and to work together to overcome them.

There have been women like Suzette Jordan and Suhaila Abdulali who have called out the stigma survivors of gender-based violence face. International Women’s Day is about acknowledging women like them, and all those fighting and resisting everyday patriarchy through small acts and in silent ways. It is not about spa discounts and role reversals, it is not just another day in the calendar after which everything goes back to usual; it is about a movement for equality and rights.

Video by Video Volunteers’ Community Correspondents Anil Kumar Mishra, Jahanara Ansari and Neelam

Article by Alankrita Anand, with inputs from Shreya Kalra

This story has been co-published with The Quint.

Fixing India| Catching A Human Trafficker| Featuring Navita Devi|

Because of Navita's determination and bravery, a human trafficking agent is being the bars, and the girls have returned to their homes.This is how our CC’s are helping raise issues and finding solutions.

Self-Help groups unable to reach their potential

In Udaipur village of Harhua block of Varanasi district, the Mahalaxmi Self Help Group was formed 3 years ago, but they could not operate independently, because of the high handedness of the village head and the laxity of the Government officials.